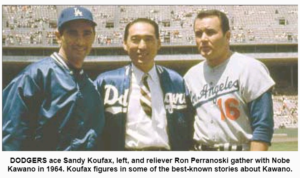

On June 18, 2022, Sandy Koufax was honored when his statue was unveiled at Dodger Stadium along with the earlier placed Jackie Robinson statue. At the ceremony, after being praised by many, Koufax addressed the assembled crowd and in his typical dignified and understated way, he deflected attention off himself and thanked various coaches and teammates, paying special tribute to Jackie Robinson. As you would expect, many great names from the past were acknowledged. As he mentioned each of these he also took time to mention one individual who did not live in the limelight: “Inside the clubhouse, our equipment manager and also good friend was Nobe Kawano.”

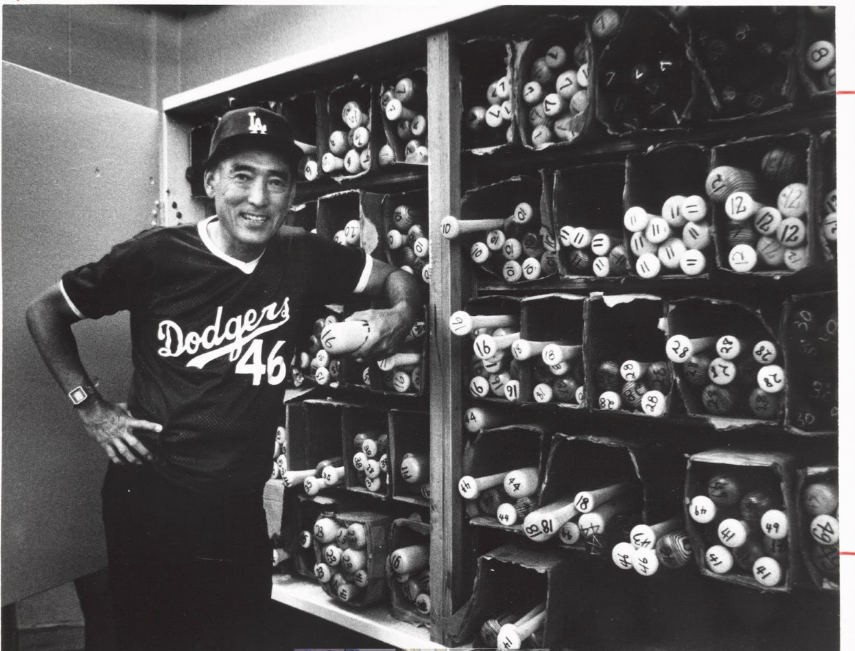

I have to admit, I had not thought of Nobe Kawano in a very long time, nor had I heard his name mentioned in many, many years. For you younger readers, Nobe Kawano was not a Star Wars character. Rather, Nobe was a dedicated man, who loved baseball and who labored tirelessly for the Dodgers behind the scenes, largely unnoticed by Dodger fans. Nobe worked for the Dodgers as the equipment/clubhouse manager for 32 years, beginning his Dodger career in 1959 and retiring in 1991.

Jeff asked if I would be willing to write an article on either Norm Sherry or Nobe Kawano. I chose to write this article about Nobe Kawano. Partly, because I’ve always had a fascination with and the deepest respect for those who “work behind the scenes” in relative anonymity. In my law career I have always made it a point to get to know the courtroom assistants, the bailiffs and court reporters on a first name basis and to express my appreciation to them for all they do to make my job easier. I was also curious about what was it about Nobe that caused Sandy Koufax to remember him as a friend at such a special time.

Working in the bowels of the Colosseum and Dodger Stadium, Nobe Kawano played a significant part in the evolution of Sandy Koufax as the legend he became. In 1960, Koufax suffered through an uncharacteristic 8-13 season. Frustrated, Koufax tossed his gear into the garbage, vowing to return to college to study architecture.

As Koufax biographer, Jane Leavey, writes:

“After the Dodgers’ final game in 1960, he (Koufax) tossed his gloves, his spikes and his dreams into the trash bin, keeping one mitt in case he wanted to play softball in the park on a Sunday afternoon. Nobe Kawano, the clubhouse man, watched as he threw his career away. ‘If you want to quit, go ahead,’ Kawano said. ‘But I wish you’d leave your arm.”

The next spring, after his temper had cooled, Koufax reported to camp at Vero Beach, Fla.,

and found all his things stacked neatly in his locker. Nobe had picked them out of the

trash. Nobe simply told Koufax, “I thought you might need these.”

Although there is little information to be found on him, Nobe’s story, albeit simple, is truly fascinating. Nobe Kawano was born on April 16, 1923, in Seattle, Washington. Nobe’s older brother was Yosh Kawano, who is a legend in Chicago Cub lore, having worked as the Cubbies’ clubhouse manager for over 60 years. The Kawano family moved to Southern California when the boys were young. They loved baseball and played the game voraciously. They were both much sought after players in the local community parks. Unfortunately, because they were of Japanese descent, the opportunities for them to play the game at a level above sandlot was virtually nonexistent due to the prejudices present in society during that era.

The Kawano brothers got their start in baseball, when Yosh started out as a spring training bat boy for the White Sox in Pasadena, Calif., during the late 1930s. Apparently, Yosh and Nobe would regularly hang around the old Wrigley Field in Los Angeles, which at the time was the home to minor league baseball, riding their bikes from Boyle Heights virtually every day. The story is told that as a 15 year old, Yosh Kawano stowed away on the ferry transporting Cubs’ players and executives to the team’s spring training camp on Catalina Island. He was discovered by a Cubs’ executive and the executive suggested putting Yosh to work shining shoes for ballplayers as penance. Apparently he was so good at it, that he was allowed to do odds and ends for the club, later latching on with Cubs in a full time capacity.

Despite working for the Cubs, when World War II came, Yosh and Nobe (along with their family) were among the more than 100,000 people of Japanese ancestry incarcerated in camps by the U.S. government. Records show Yosh and Nobe were sent to the Colorado River “relocation project” camp in Arizona, which was known as the Poston Internment Camp, the largest of the ten camps the government created to house the Japanese-Americans. Poston Internment Camp was located in the desert of southwestern Arizona on the Colorado River Indian Reservation against the wishes of the Mohave, Hopi, and Navajo tribes who lived there. While deemed a threat to national security, it turns out, according to archival records, that Yosh and Nobe had visited Japan just once before. Despite how cruelly they were treated, the were Americans through and through.

Ironically, Poston Internment Camp was built by Del Webb, an incredibly wealthy developer (famous in Riverside County for developing the retirement community known as “Sun City”) and war contractor, who went on to buy the New York Yankees in 1945. Apparently, some people profited from the internments.

Yosh Kawano’s Cubs’ connection ultimately aided his release, when William Wrigley wrote to vouch for his character and request his presence with the ball club. After his release, he worked for the Cubs in 1943 and 1944, before he was drafted into the U.S. Army. He was deployed overseas with the Army, where he worked as a translator in the Philippines and New Guinea.

Nobe, whose given name is Nobu, was classified as 4F and joined the U.S. Merchant Marine, running supplies between the U.S. and Great Britain. According to an article written by his daughter, Hana Kawano, even though Nobe did not serve on the frontlines, his job was neither easy nor safe, as her father had to constantly journey through U-boat-infested waters.

After the war, Nobe began looking after equipment for the Hollywood Stars, working as their equipment/clubhouse assistant. He worked for them from 1941 through 1956. He also worked one year for the Salt Lake City Bees minor league club. When the Dodgers moved out west, They hired Nobe to be their equipment/clubhouse manager. He served in that capacity from 1959 through 1991.

We’re in the midst of trade speculation season, wondering who the Dodgers might acquire before the deadline. But back then, Tommy Lasorda made it clear that Nobe was one of the few members of Los Angeles Dodgers who never had to worry about being traded. “I wouldn’t trade Nobe Kawano for any equipment manager in baseball” Lasorda said.

Mind you, being a clubhouse manager isn’t particularly a glorious job. Nobe’s job was to keep uniforms clean, keep the lockers straight, order gloves and shoes for the players, lay out the pre and post game meals. He would sort through the mail, sweep the floors, handle front office requests for baseballs, order sodas, ice cream and other food items, pack the bags for the next road trip, do the laundry and keep the clubhouse clean. Nobe kept everything ready and worked tirelessly to meet the needs of the players. One of his most important jobs was maintaining Kawano’s Kitchen, which was right next to the player’s locker room. His dedication to his job was such that when he bought a new refrigerator and freezer for his wife, he brought his wife’s old refrigerator and freezer to be set up in Kawano’s Kitchen to help assist in the daily ice-cream and snack raids that would take place before and after the games. Occasionally, Nobe’s wife would bake an apple pie and bring it to the stadium. If you don’t think that will bring a pitcher who just got shelled in the third inning out of the doldrums, imagine his pain on an empty stomach. In one of the only interviews of Nobe that I could find on-line, which was conducted by Jeane Hoffman in May 1960, Nobe shared “I post prices on the wall. The players mark down what they owe and keep their own financial box score.” Nobe added, “they are all good piece-mealers, except Chuck Essegian, I’m worried about him.” As I write this, I’m reminded that baseball was much simpler then; it was not yet a multibillion dollar business.

Detail takes on immense proportions for a man who must outfit 24 ballplayers 162 times a year (not counting the postseason). According to Dodger estimates, the team carts around nearly 2,500 pounds of uniforms and equipment, including caps, shoes, belts, jackets and protective gear.

As baseball grew more sophisticated, Kawano’s job got much harder. In an interview in “Dodger Blue,” the team’s in-house newsletter, Nobe said,

“In the olden days, the average player only had two pairs of shoes, a couple gloves, a couple sweatshirts, no helmets. Now they have things like batting gloves and some players have as many as 20 pairs of shoes.”

Nobe would regularly work 12 or more hours a day. Nobe traveled with the team, spending long hours away from his wife and three children.

As his daughter put it:

“In that capacity, Dad was often on the road. Bonding time with him was limited to only three months during the year. Most people probably pitied me and my siblings, but I didn’t feel sad. I knew that Dad was happy, worked a job he loved, and was an indispensable part of the team.

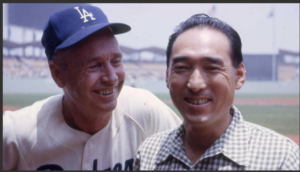

The players loved Nobe and appreciated what he did for the team. Steve Garvey, who once worked as a bat boy for Nobe Kawano, called him “the quintessential clubhouse man.” Nobe

approached this work in a quiet, meticulous manner, arriving at the ballpark hours before the first pitch and staying late into the night. “The word is dedicated,” says Rick Monday, who came to know both Nobe and his brother Yosh while playing for the Dodgers and Cubs. “Both of them took their jobs very seriously.” Despite the diligence he brought to the job, Nobe also had a funny side to him. One example, everyone knew that Tommy Lasorda was very sensitive about his weight, so one time Nobe and first baseman Steve Garvey collaborated to change the name on the back of the manager’s uniform to “Lasagna.” Lasorda discovered the switch only after he got dressed and heard laughter flittering through the clubhouse. I can imagine Lasorda wasn’t too happy about that.

Nobe’s career ended quietly after the 1991 season, when he retired at 68. He settled into a top-floor apartment in a building he constructed just outside the entrance to the Dodger Stadium parking lot. Though he did not get a splashy send-off for his retirement, his value to the team was evident. Rick Monday recalled a time a few years before he retired, when the Dodgers were in Pittsburgh on a road trip. The players boarded a bus to return to their hotel. Nobe almost never rode with them, he either stayed late to finish his chores or found another way back. As Monday put it,

“We’re crossing the bridge to go downtown and, at a red light, we pull right behind a city bus, I look up and Nobe Kawano is on that bus. He took a city bus.” At the next stop, the Monday jumped out to retrieve the clubhouse manager, saying: “You’re a Dodger. You travel with us.” “When he got on, all the guys started clapping,” Monday says. “It was a real ovation and he started to giggle.”

Nobe and his brother Yosh, the two kids who loved to play baseball both had long and illustrious careers in baseball, albeit not as players. Yosh spent 68 years with the Cubs. Among other things he was known for his ever present floppy white tennis hat that became his trademark in Chicago. That hat made its way into Cooperstown. Nobe worked with the Dodgers for 38 years. While Yosh had the longer career, one thing he never got to experience was the Cubbies winning a world series. Whereas Nobe received a ½ World Series share in 1959, his first year with the Dodgers. Half of the $11,231.00 paid to the players was big money back then.

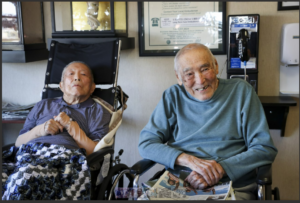

Yosh was still alive in 2016 when the Cubs won the World Series. He was also presented with a World Series ring, however, by then he had lost the ability to speak and his memory, as with Nobe’s, had been ravished by dementia and Parkinson’s disease. It’s unfortunate that they weren’t able to tell more of their stories before illness set in. I’m sure they had some tales to tell. But then again, being the honorable men they were, I doubt that they would violate their loyalty to the players or team by sharing anything inappropriate or personal.

As seemed fitting, the Kawano brothers spent the latter several years of their lives in the same nursing home in Lincoln Heights, a short drive from that apartment where Nobe lived with his family. Yosh Kawano died on June 25, 2018 (I write this on the 4th anniversary of his death) after a long battle with Parkinson’s disease. He was 97 years old when he died. On July 27, 2018, a few days after attending his brothers funeral, Nobe died of respiratory problems. He was 95 years old.

In his simple way, Nobe Kawano is a baseball giant. Like many of the game’s great players, he worked his way up through the farm system of a major team and he became an integral part of a baseball dynasty. I’m glad to have spent some hours of research getting to know more about him and his wonderful story. People like Nobe don’t come along that often.

Great story told awesomely.

Rob,

Thank you for writing this. After doing the Sandy Koufax research I was reminded just how much of a true LAD Nobe was. I just knew that Nobe’s story had to be told, and you did it expertly. This is a fantastic piece about a great Dodger.

A clubhouse legend.

Great read. Thanks Rob.

Read this at The Athletic this morning.

We need to examine how Major League Baseball’s 100-year-old antitrust exemption is affecting the operation of Minor League baseball teams and the ability of Minor League ballplayers to make a decent living,” said Durbin, the U.S. Senate Majority Whip, in a statement. “This bipartisan request for information will help inform the Committee about the impact of this exemption, especially when it comes to Minor League and international prospects. We need to make sure that all professional ballplayers get to play on a fair and level field.”

Yeah, let the Senate look into this, because they are so good at getting things done.

Thanks for the kind comments folks.

I’m working on some articles on that examine the reserve clause, starting with a profile of Andy Messersmith, that I hope to expand into the anti-trust exemption. Like you Badger, I don’t believe the government will do anything about it. Could our skepticism about the Senate have anything to do with having spent time in the Marines?

Good observation Rob. The answer is yes. Believing their lies damm near cost me my life. I haven’t forgotten. And nothing has changed.

Andy was from my neighborhood, a few years in front of me. I didn’t know him well, but I don’t have anything nice to say about him.

Great article Rob. Very fun and informative read about a part of Dodger history I had not heard before. Thanks.

Kenley Jansen is back on the IL with an irregular heartbeat. Many prayers for you big man. Get well.🙏

Freeman has fired his agents, apparently upset how they handled negotiations with Atlanta.

Maybe we should trade Freddie back to the Braves in exchange for Matt Olson. Win, win.

As of now, Mets catcher Francisco Álvarez looks like the favorite. Just 20 years old, he’s batting .280/.365/.564 in 62 contests, ranking third in the Eastern League in homers (17) and fifth in OPS (.929) as the youngest regular (age 20) in the Double-A circuit. The parent club is obviously in it to win it and is getting the second-worst offensive production from catchers in the Majors, so I wonder if we might see Álvarez in New York before season’s end.

Interesting on the timing of the firing and the meaning. Did his agent not give him the most up to date offers? Could he have stayed in Atlanta and the agent did not get the message to Freddie? Things moved fast after the lockout ended, and Freddie should have told his agent that he wanted to stay in Atlanta (if that is the case)…make it happen.

And then there was this comment from Clayton Kershaw:

“It was very cool (to see Freeman’s reception Friday night),” Kershaw told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “He’s obviously been a big contributor for our team. And I hope we’re not second fiddle. It’s a pretty special team over here, too. I think whenever he gets comfortable over here, he’ll really enjoy it. It was a good night for him (Friday).”

And this tweet from Chelsea Freeman:

I have no idea what any of it means, but the timing sure does stink.

I trust the crying will stop now. He can live there in the off season and retire there when he’s 37 if he chooses. I’m thinking $270 million goes farther in Georgia than it does in LA. In the mean time, how we win the West and then beat the Braves in the playoffs.

The Braves have who they want with Olson. They got younger and cheaper and Olson is a local kid. Freddie went home. Hopefully he can produce until he’s 37.

Oakland to Vegas? Yes.

I could live with that. Freddie should have waited a couple of weeks to fire the agent. Let the silliness of his return to Atlanta die down.

I think Freeman, while leaving a piece of his soul in Atlanta, will give the Dodgers his very best. That piece of soul will find its way back to LA soon enough.

I loved growing up in Southern California. I moved my family to Oregon because it had cleaner air and less crowds. But it took me a few years before I let California go. I was ready to leave. Freeman wasn’t. I am not ready to return. Maybe Freeman wasn’t either.

Regarding Freeman and where he wants to be, I don’t give any energy to it. Yes, I am writing about here but just to be part of the conversation.

I certainly remember the air here in the 60s and early 70s. It’s much better now but after being gone 48 years it’s tough to be among the crowds again. I’ve got friends and family in Oregon, but I still think Northern California feels like home, though it’s been 14 years since I lived there.

My brother said Covid is spiking again in Southern Oregon. Damm. It ain’t going away anytime soon.

Not Kershaw’s night. Offense still asleep, but that was an impressive shot by Muncy.

What a great story Rob. I too love those behind the scenes stories. They were two amazing men that tend to get forgotten.