In my last article on this subject, I introduced you to the early history of the Reserve Clause and how the players and owners initially dealt with it in the courts. In this article, I hope to lay out a little of the history on how Major League baseball received and, until now, has kept an Anti-Trust Exemption through decisions made by the Supreme Court. First off, I will admit that I borrowed heavily from an article written for the Federal Judicial Center, by Jake Kobrick, an Associate Historian entitled “Baseball’s Reserve Clause and the “Antitrust Exemption.’” If it sounds somewhat intelligent or interesting, the information came from Kobrick, guaranteed.

In my last article, we left off with the case of American League Baseball Club v. Chase, 149 N.Y.S. 6 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1914). This was dispute involving Hal Chase, a star first baseman who moved from the Chicago White Sox of the American League to the Buffalo Buff-Feds of the Federal League. The White Sox sought to enjoin Chase from switching leagues. In his defense, Chase argued that baseball violated federal antitrust laws. The Judge ruled that professional baseball could not be regulated by Congress because it was not interstate commerce, but that baseball nevertheless constituted a monopoly in violation of the state’s common law. The Judge based his decision on the following reasoning (dubious as it is): “Baseball is an amusement, a sport, a game that . . . is not a commodity or an article of merchandise subject to the regulation of congress . . . .”

In the owner’s mind, this seemed to bring some relief, however, the newly formed Federal League had other ideas. The Federal League began play in 1913 as a six-team minor league. In 1914 and 1915 the Federal League declared itself a major league and sought to challenge the National League and the American League. Of course, their detractors called it an “outlaw” league. Among its main attraction was the fact that the Federal League allowed players to avoid the restrictions of the other major leagues’ reserve clause. The resulting competition of another, better paying, league caused players’ salaries to skyrocket. As you can imagine this did not make the American League and the National League owners too happy.

But alas, litigation such as the afore mentioned Chase case, the continual interference with their players, and the unsustainable business plan of paying higher contracts to aging star players, caused the Federal league to fold in 1915. Not to be deterred though, the Federal League then filed a lawsuit against the National and American Leagues in federal court in Illinois, alleging that these leagues amounted to a combination in violation of federal and state antitrust laws. (Federal Baseball Club, Inc. v. National League of Prof’l Baseball Clubs, 259 U.S. 200, 208-09, 1922).

As fate would have it, the suit was assigned to Kenesaw Mountain Landis, a federal judge sitting in Chicago. As some of you might know, Landis would go on to become baseball’s first commissioner, serving from 1920 to 1944. Judge Landis was a keen baseball fan, and he was apparently concerned that a decision adverse to the major leagues would undermine the game. During trial, he declared from the bench that “any blows at . . . baseball would be regarded by this court as a blow to a national institution.” Judge Landis did not announce a decision for over a year. During the time that the case languished before him, and being in dire financial straits, the Federal League agreed in 1916 to a settlement with the National and American Leagues. As part of the settlement, the league would go out of business, but five of its teams located in major cities would be absorbed into the existing leagues. When the parties appeared before Judge Landis to inform him that the suit had been settled, the judge admitted that he had delayed a decision because he would have found in favor of the Federal League but feared that the result would have destroyed professional baseball.

Unfortunately for some, the benefits of the settlement were not evenly distributed among participants in the Federal League. The established leagues bought out owners with competing clubs in major league cities. They offered a few owners the opportunity to purchase interests in existing major league clubs. Charles Weeghman of Chicago, for example, bought the Cubs and moved them into the North Side ballpark he had built for his ChiFeds, now named Wrigley Field. Phil Ball of the St. Louis Feds, bought the American League Browns. While these folks made out well, three franchises—including the two that were publicly owned, Baltimore and Buffalo were left to twist in the wind.

Not surprisingly, Ned Hanlon, owner of the Baltimore Terrapins, felt particularly aggrieved by the settlement. He was offered $50,000.00, but rejected it out of hand. Hanlon had a long, successful history of involvement in the game, as a player, manager, and owner, and Baltimore had enjoyed a glorious tradition of baseball play. It had shared possession of the National League pennant with the Boston Beaneaters throughout the 1890s. Not motivated by money, Hanlon and his co-owners remained focused on putting a major league baseball team in Baltimore. The owners of the American and National League teams refused, however, believing that major league baseball in Baltimore would be a financial failure. Charles Comiskey, owner of the White Sox best described the National and American Leagues’ attitude towards Baltimore: “Baltimore is a minor league city and not a hell of a good one at that.”

The following year, the Terrapins’ owners filed suit against the American and National Leagues and their member clubs, alleging that they had conspired to monopolize the business of professional baseball. After a 1919 trial, Justice Wendell Phillips Stafford of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia (now the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia) ruled baseball an illegal monopoly. The jury awarded the Baltimore club $80,000 in damages, which became $240,000 under the Sherman Act’s treble damages provision. On appeal, the Court of Appeals of the District of Columbia (now the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit) reversed the judgment on the grounds that baseball did not constitute interstate commerce and was therefore outside the scope of the Sherman Act. The case then proceeded to the Supreme Court, which affirmed the appellate court’s ruling in 1922. “The business,” wrote Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in the Court’s majority opinion, “is giving exhibitions of base ball, which are purely state affairs.” “The interstate travel that was necessary to facilitate the games,” Justice Holmes continued, “was incidental to the games themselves, which occurred in a single location. Moreover, because the product being sold was the personal effort of the players, and not a commodity, the games would not be called trade or commerce in the commonly accepted use of those words.” Justice Holmes’ opinion was subjected to criticism, both immediately and for decades afterwards, by those who believed that the Court misunderstood the nature of professional baseball or had engaged in sophistry to protect it. (Federal Baseball Club, Inc. v. National League of Prof’l Baseball Clubs, 259 U.S. 200, 208-09, 1922) The Supreme Court’s decision in Federal Baseball Club is often characterized as creating baseball’s antitrust exemption. However, the case created no special exemption. To the contrary, the Court held that professional baseball was neither interstate nor commerce and was therefore outside the scope of the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890.

Thereafter, as the business of baseball continued to grow, and its games were broadcast throughout the country, first on radio and later on television, the Court’s decision was increasingly seen as dubious, at best. A non Supreme Court case in 1949 seemed to suggest just that.

In 1949, Major League Baseball and it’s commissioner, Happy Chandler were sued by Danny Gardella. Gardella played for the New York Giants of the National League in 1944–1945 before leaving to play professional baseball in Mexico. Because he had been under contract to play exclusively for the Giants, he was barred for several years from returning to the major leagues in the United States. Gardella sued the Giants and the National League, alleging that they had deprived him of his livelihood and monopolized baseball in violation of the Sherman and Clayton Antitrust Acts. The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York dismissed the complaint, holding that it lacked jurisdiction over the case in accordance with the Supreme Court’s decision in Federal Baseball Club. However, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit voted 2-1 to remand the case to the district court for trial. Judge Harrie Chase voted to affirm the district court’s ruling, believing Federal Baseball Club required that result. Judge Chase added that even if Federal Baseball Club was distinguishable from the case at hand, Gardella’s services as a baseball player were not items of trade or commerce under the antitrust laws. Judges Learned Hand and Jerome Frank disagreed, however, on the grounds that circumstances had changed since 1922. Judge Frank believed that television and radio broadcasting of baseball games was an essential part of the business and sufficient reason to deem baseball interstate commerce. Judge Hand tentatively agreed but felt this was a factual matter that should be resolved at trial. (Gardella v. Chandler, 172 F. 2nd 402 (2d Cir. 1949)).

Baseball officials decided not to appeal the court’s ruling to the Supreme Court for fear that Federal Baseball Club would be overturned. Gardella received a settlement, and the suspensions of other players who had jumped to the Mexican League were rescinded. Gardella was the first case in which a federal court suggested that professional baseball might be subject to the antitrust laws.

Baseball became more and more concerned about its ant-trust status. As a result, there was much at stake when the Supreme Court next had an opportunity to review its earlier decision in Federal Baseball Club, a decision many considered outmoded. A Court ruling that the 1922 case was decided wrongly could open baseball to thirty years of retroactive antitrust liability, potentially threatening the viability of the sport. To the relief of professional baseball owners, when given the chance, the Supreme Court left it to Congress to decide whether or not professional baseball would be subject to federal antitrust laws. Thus, if Congress were to pass legislation, it would apply only prospectively, and baseball would not suffer harm for having relied on the earlier Court decision.

In 1953, the Supreme Court in Toolson v. New York Yankees, Inc., 346 U.S. 356 (1953) decided that . . .

George Toolson was a pitcher for a minor league team in Newark, New Jersey, that was affiliated with the New York Yankees. When the Yankees assigned Toolson to a lower-level team in Binghamton, New York, he refused to report. Pursuant to the terms of his contract, the Yankees then declared him ineligible to play professional baseball. Toolson sued the Yankees, claiming that they were violating the antitrust laws by refusing to let him play for another team. The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California dismissed the case, ruling in accordance with the holding in Federal Baseball Club that baseball was not subject to the antitrust laws. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit affirmed after which Toolson was argued before the Supreme Court along with two similar cases.

The issue was clearly framed for the Supreme Court in Toolson, and it had three obvious choices: (1) uphold the dismissal on the strength of Federal Baseball, as had every lower court except the Second Circuit; (2) reverse the dismissal based on the reasoning of Learned Hand in Gardella; or (3) overrule Federal Baseball for the reasons suggested by Judge Frank and others. But the Court took none of these courses. Instead, it took the first step in the greatest bait-and-switch scheme in the history of the Supreme Court. The Court affirmed the ruling below on the authority of Federal Baseball Club. The Toolson decision was handed down per curium. In a single short paragraph, the Court wrote:

“The judgments in these cases are affirmed on the authority of Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League of Professional Baseball Clubs, 259 U. S. 200, so far as that decision determines that Congress had no intention of including the business of baseball within the scope of the federal antitrust laws. In Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League of Professional Baseball Clubs, 259 U. S. 200,this Court held that the business of providing public baseball games for profit between clubs of professional baseball players was not within the scope of the federal antitrust laws. Congress has had the ruling under consideration, but has not seen fit to bring such business under these laws by legislation having prospective effect. The business has thus been left for thirty years to develop on the understanding that it was not subject to existing antitrust legislation. The present cases ask us to overrule the prior decision and, with retrospective effect, hold the legislation applicable. We think that, if there are evils in this field which now warrant application to it of the antitrust laws, it should be by legislation. Without reexamination of the underlying issues, the judgments below are affirmed on the authority of Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League of Professional Baseball Clubs, supra, so far as that decision determines that Congress had no intention of including the business of baseball within the scope of the federal antitrust laws.”

Fact is, you can look at the Federal Baseball Club opinion as long as you like, but there is no suggestion – express or implied – that the Congress of 1890 intentionally excluded baseball from the Sherman Act. There, pulled out of thin air, is your Anti-Trust Exemption. The Court’s rationale, that Congress could have regulated baseball but had chosen not to, was the source of baseball’s “exemption” from federal antitrust law. Although Congress subsequently held hearings on the issue and considered several legislative proposals, it took no action. Baseball remained an anomaly as other major sports were subjected to antitrust litigation throughout the second half of the twentieth century. (Federal court decisions of 1955, 1957, 1971, and 1972 established that antitrust laws applied to professional boxing, football, basketball, and hockey, respectively, despite what many saw as the lack of a meaningful distinction between those enterprises and major league baseball.)

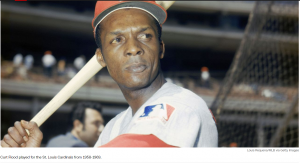

The next to invite MLB to come dance with the Supremes, was Curt Flood. Curt Flood an outfielder with the St. Louis Cardinals was one of major league baseball’s best players during the 1960s. In 1969, as Flood was nearing the end of his career, the Cardinals traded Flood to the Philadelphia Phillies. Not wishing to go to Philadelphia, Flood appealed to Commissioner Bowie Kuhn to declare him a free agent and allow him to sign a new contract with another team.

“After 12 years in the Major Leagues,” he wrote, “I do not feel I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes.”

When his request was refused on the basis of baseball’s reserve clause, Flood filed an antitrust suit in federal court in New York City, naming Kuhn, the presidents of the American and National Leagues, and all major league teams as defendants. (Flood brought other claims as well, including one for involuntary servitude in violation of the Thirteenth Amendment, which the courts found without merit.) The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York found for the defendants, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed. In his opinion affirming the Second Circuit Justice Harry Blackmun acknowledged that baseball was a business operating in interstate commerce, and that the Federal Baseball Club and Toolson cases

“have become an aberration confined to baseball.” Nevertheless, he wrote, “[i]t is an aberration that has been with us now for half a century, one heretofore deemed fully entitled to the benefit of stare decisis, and one that has survived the Court’s expanding concept of interstate commerce. It rests on a recognition of baseball’s unique characteristics and needs.”

Because Congress had considered several bills regarding the application of the antitrust laws to baseball but never enacted one, Blackmun concluded that legislators still had no intent to alter the result of the earlier baseball cases. And, as the Court had done in Toolson, he expressed concern about the retroactive nature of a decision overturning those cases. Justices William Douglas and William Brennan dissented from the Court’s ruling, as Douglas called Federal Baseball Club “a derelict in the stream of law that we, its creator, should remove.” Although Douglas had joined the Court’s opinion in Toolson, he admitted that he had “lived to regret it” and wished “to correct what I believe to be its fundamental error.”

By the time Curt Flood lost his case before the Supreme Court, he had already retired from professional baseball. Within a very short time, however, labor relations between players and owners began to undergo dramatic changes spurred by the recent arrival in baseball of modern labor practices: uionization, collective bargaining, and arbitration. In 1966, players unionized, forming the MLBPA, and in 1968 the union negotiated its first CBA with the owners of the major league franchises. The 1973 CBA vindicated Flood’s position that a veteran player should not be traded against his will, providing that a player with ten years of experience who had played with the same team for five years was entitled to veto a trade.

In 1998 Congress enacted the Curt Flood Act. However this act explicitly excluded from its scope matters relating to minor league teams and players; franchise expansion, relocation, and ownership; broadcasting; umpires; and the conduct of people not directly employed in major league baseball. The antitrust status of the business of baseball as a whole thus remained unaddressed by federal legislation, leaving the scope of the exemption to the interpretations of federal and state courts. More on that in my next, and last, article on this subject. I will also touch upon the recent issues brewing with minor league baseball and its unionization and how MLB is responding to these matters. There’s always more than meets the eye.

Till then, turn on some Diana Ross and the Supremes and dance around the family room!!

Good work Rob.

Curt Flood – one person can make a difference.

Baseball should retire his number if it hasn’t already and play one game a year where all players wear his number like they do number 42.

Good read Rob.

Yes, advancements in baseball were quite slow. But, so were/are many other social and economic advancements. And these guys do play a game for a living. Would most of America trade places with them? Who didn’t love playing baseball as a kid. I played every chance I got. Hell I played into my 50s and never got paid a dime. The battles continue and good on all those who put up a fight against injustice.

I wonder when some of our starters will start getting days off?

As I see it, it was a confluence of some courageous players, Curt Flood and later Andy Messersmith & Dave McNally, and powerful and committed decision makers, Marvin Miller and Bowie Kuhn, who were willing to make changes. I do not think these changes happen if either William Eckert or Ford Frick were still commissioner. Bowie Kuhn was the appropriate person at the MLB helm. He deftly convinced the owners that the changes were better than losing the anti-trust exemption. Marvin Miller was the right person at the right time for the players.

The parties were smart enough to stay out of court and hire a smart and courageous arbitrator, Peter Seitz, who skillfully negotiated the end of the reserve clause Donald Fehr assisted MLBPA in the Messersmith/McNally arbitration, and Miller later hired him to be the Association’s general counsel.

It was just a time in history where the stars aligned and change was made. Not all of the parties were liked, and most were hated. But they persevered and made history. I cannot see any of this happening if it were Tony Clark and Rob Manfred at their respective helms. They are a bad joke compared to Marvin Miller and Bowie Kuhn.

Danny Duffy and Victor Gonzalez are done for the year. The Dodgers pulled the plug on their rehab. The reason for VGon was “fatigue” and Duffy was “not recovering”. IMO, this was more of an opportunity to stop an impending roster crunch that was just about to blossom. That now leaves one 60 man IL who needs to come off (Tommy Kahnle) and only one player who will need to be DFA’d…probably Heath Hembree, but I have no insight.

I do think the resurgence of Phil Bickford since returning from OKC had a lot behind the decision. Since returning 09/01/2022, Bickford has been in 5 games, 5.2 IP, 0 runs, 4 hits, 1 BB, 10 K. That makes his scoreless streak to 7 games and 7.2 IP.

I don’t expect to see Duffy, but VGon suddenly getting “unfatigued” wouldn’t shock me. This allows them to reset the rehab on him so, if they actually want to bring him back, they’ll be able to do it anytime between now and the playoffs.

If Victor’s arm hadn’t had that sudden setback (after his rehab was going quite well), they would have had to add him to the 40-man this week. They still might prefer him to Price on the playoff roster as the third lefty reliever along with Ferguson and Vesia. And, of course, they need to decide what they’re going to do with Heaney (starter, reliever, both?).